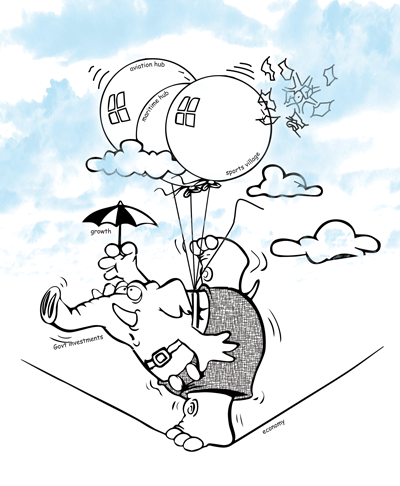

A Circus of White Elephants

The deep South’s tranquillity makes it a hotspot for big game enthusiasts. Its expansive national parks are among the best places in the world to spot leopards while elephants are abundant even in areas far outside the protection of wildlife rangers. New government policy is now aiming to add concrete white elephants to the list […]

The deep South’s tranquillity makes it a hotspot for big game enthusiasts. Its expansive national parks are among the best places in the world to spot leopards while elephants are abundant even in areas far outside the protection of wildlife rangers. New government policy is now aiming to add concrete white elephants to the list of attractions in the Southern tip of Sri Lanka. For all their faults, the British left an amazing legacy of infrastructure, but all that is now a century old. In the decades since, Sri Lanka’s investment in infrastructure has been anaemic. Poor roads, outdated rail transport, overcrowded public transport and crumbling public buildings are an expensive burden. Infrastructure deficiency ills filter down to every citizen and add billions in extra costs and lost productivity.

So it’s difficult to miss the enthusiasm with which the rural Hambantota district is being promoted as Sri Lanka’s next global hub. Some of the infrastructure, like a sea port, would make long term sense. However rigorous sequencing of investments of heavy industry and raw material processing, like oil refineries, alongside, would have ensured the port started contributing to the economy sooner. Until industries locate alongside and ships sail in raw materials and carry out finished goods, Sri Lanka’s showpiece port will only be as useful as can be a giant water filled hole in the ground. However, grand infrastructure is long term in nature and greater things may be expected of a bulk cargo and bunkering port on Sri Lanka’s Southern tip. The same enthusiasm for other infrastructure projects would be misplaced.

Those keen on muddying the debate argue that only elitists and declinists would criticise investment in rural infrastructure. Rural infrastructure like roads, better schools and hospitals indeed improves the lives of people and also make rural districts attractive for greater private investment. However, big infrastructure projects, like airports and multi-billion rupee sport stadia, should pass tests of utility before ground is broken and public money spent.

Firstly, long term infrastructure assets need to be matched with proven long term demand. The chunky nature of the investment compared to the gradual nature of the demand for it, make rigorous analysis of its future utilization essential. An analysis will show that there are no viable levels of traffic projected for the almost complete Hambantota airport. Airports and airlines operate on a hub and spoke sort of model. A country the size of Sri Lanka can at best sustain one hub airport and a number of regional ones which feed traffic to the main hub. The same hub will be fed by the international network, and the resulting scale makes operations efficient and air travel affordable. Since no airline plans to hub out of Hambantota, the new airport will automatically be relegated to a regional one.

Also the smallest jets operated by international airlines carry 180 people and passenger traffic will have to top one thousand daily arrivals and departures, to fill three daily flights to three international destinations being projected by the airports authority. So far, no traffic projection exists to show that Southern Sri Lanka generates 350,000 travellers to any three international destinations in a year.

Big airport projects are notorious for their boondoggle tendencies. Montréal International, the largest airport in the world in terms of surface area ever envisioned, had to be shut for passenger traffic because its distant location and lack of transport links made it unpopular with airlines and travellers. Several airports in Spain are considered as white elephants including Ciudad Real Airport, which closed in 2012, only four years after opening. In a similar situation fell the Castellón Airport north of Valencia and the Huesca-Pirineos Airport.

Constraints at the existing terminal at the Katunayake airport during peak hours are undermining SriLankan Airlines growth. Airport authorities were mulling turning an old kitchen in to a passenger terminal to overcome the bottleneck. Meanwhile, state of the art passenger terminal capacity will soon be available, but unfortunately for SriLankan airlines, some 250 kilometres away from its hub airport.

It’s argued that underutilization and low returns in the short term is a necessary evil. This is indeed the second test; the economic rate of return of competing projects. The Hambantota airport at $282 million, the cricket stadium and sports city at $130 million and an international convention centre at $20 million are all projects that have already been completed or will be during the next few years. If not these in Hambantota, what else could Sri Lanka have done with $432 million offering a greater economic return?

It could have built an almost 15 kilometre metro system including rolling stock, signalling, stations and the whole works, based on the $32 million a kilometre it cost New Delhi to build similar world class infrastructure. The economic rate of return of a metro is very high, the entire city benefits, pollution levels fall as fewer people travel on the road, also lowering maintenance cost and saving time. Productivity is higher because there are fewer traffic jams and lower fuel usage. A metro, will from day one, likely be fully utilized. Add more financing, perhaps from a multilateral lender (the ADB was the largest financier of the Delhi Metro first phase) and a reasonable sized MRT system could be de-clogging Colombo and benefiting many of the three million people who travel in to, and within the city every workday. If engineering work on a metro had commenced about the same time instead of the Hambantota airport, Colombo may have in a few years sighed with relief.

As unwieldy traffic snarls descend Sri Lanka’s economic hub Colombo in to dystopia, its rulers have chosen instead to build stadia, airports and convention centres that will for the most part be unused. A traffic study by Delhi Metro engineers identified a number of viable routes for an MRT connecting Colombo to the suburbs some years ago. A metro isn’t the only option, expressways, bottleneck busting link roads, rural schools and hospitals will all improve the lives of people and start immediately contributing to the economy. The Southern Expressway cost $700 million and while funding for grand infrastructure isn’t a challenge, the government is yet to finalise funding for a highway that will link Colombo to Kandy.

The world is also replete with boondoggle sports stadia. Once a major sporting event for which the facilities are built is over, there has to be an identified sports team with a huge fan base and franchise that can make the stadium their home and host sell-out crowds for every home game. Currently there are no clubs or sports leagues that can fill stadia in population dense Colombo, leave alone Hambantota. An international cricket ground there, used only occasionally, cost $7.5 million dollars and some of its seats were cannibalised from another international cricket venue in Dambulla which has not hosted a single international fixture since.

Thirdly, it’s crucial to have citizens involved in the decision-making about deployment of scarce resources. Politicians don’t pay for infrastructure out of their pocket, so there is a tendency for pork barrel spending, a tendency to gold plate things and build bigger and stronger when smaller and lighter may just as well have worked.

Sri Lanka’s traditional donors like the World Bank or ADB, who are keen to improve rural infrastructure, may not have financed Hambantota’s grandiose infrastructure because of the obvious lack of their impact on the people of this country. The Chinese government on the other hand, which is giving loans to build many of these, doesn’t have such qualms. Their loans attract almost market rates of interest, all construction contracts are awarded to Chinese firms, all equipment, most workers and construction material also arrives from China.

China may not care if infrastructure it helps build, has any economic or utility value or if it’s purpose is to prop egos and is pork barrel spending. It will gladly gold plate any infrastructure project only caring about the loan repayment. Despite its sparse population an impressive administrative complex is under construction, perhaps an indication of a grander role the district may play in Sri Lankan national affairs in the future. Detailed Hambantota zoning plans include zones for a diplomatic enclave and areas for high income housing and chalets.

However not all government infrastructure investment is pork barrel. A genuine belief, despite repeated failure, seems to be driving investment in to areas where there is no shortage of private investors. The Ports Authority is building a new container terminal in a new extension to the Colombo port, despite plenty of private sector players willing to invest in such projects and actually pay the port authority for such concessions. Recently the Bank of Ceylon was pushed in to buying a stake in money loosing SriLankan airlines which hasn’t yielded any return for the institution.

Far murkier deals are brewing like plans to reclaim the sea to build a golf course, hotels, apartments and a Formula 1 racetrack. While the citizens of this country will have to repay the loans for reclaiming the sea, the absolute lack of transparency in how and why this is being done is shocking. Transparency in infrastructure investment is critical because people can then choose, for instance, if they want to reclaim the sea in front of Galle Face Green in Colombo to watch a formula one race or wish to use that money to improve rural schools.

Critical rural infrastructure that immediately impacts the quality of life of citizens and improves opportunities for them may not come in the shape of airports and sports stadia in the jungle. They will likely have no practical value to people except perhaps as a freak showpiece white elephant.