Big Idea - Sharing Economy - Sharing economy firm gets Rs750 million valuation three months after launch

Soon the neighbours started objecting to the dozens of cars and tuk tuks jamming the narrow lane that connected Colombo’s Marine Drive to Galle Road. When the school opposite joined in demanding an end to the frequent traffic jam on the road, Jiffry Zulfer knew they had to move. Zulfer is founder and Chief Executive […]

Soon the neighbours started objecting to the dozens of cars and tuk tuks jamming the narrow lane that connected Colombo’s Marine Drive to Galle Road. When the school opposite joined in demanding an end to the frequent traffic jam on the road, Jiffry Zulfer knew they had to move. Zulfer is founder and Chief Executive of PickMe, a mobile phone app allowing users to order a taxi, quickly.

Since it launched its services in July 2015, the firm has been nothing short of disruptive – from the scale of the traffic jam it caused on Colombo’s Retreat Road where it is located, to its incredible valuation three months after launch and how much efficiency it has extracted from the process of ordering a taxi.

Digital Mobility Solutions Lanka – the firm behind the PickMe mobile app – has replicated the now ubiquitous Uber business model with tweaks to suit Sri Lankan conditions. Its critical early success has been due to its ability to adapt a proven model to Sri Lankan market idiosyncrasies and the pace at which it has grown. PickMe does not own taxis. It just runs a network that links taxi operators who register with the company with users who book rides though its app. Anyone can register a tuk tuk, a mini car or a salon type of car. They don’t have to drive the vehicle full time either. Registered drivers log in to the system though a PickMe provided device, a smartphone restricted to its app, when they are ready to accept a hire. PickMe has been overwhelmed by the demand and has registered over 2,000 vehicles – 60% of which have been tuk tuks. They currently have a waiting list of drivers and aim to have as many as 5,000 available by end-2015. During the rest of 2015, PickMe is focused on achieving scale and introducing payments for the hires though the app, which will make it possible for the firm to earn a commission for the service it provides.

US-based Uber – which has launched across many big cities worldwide – pioneered this digital network that matches a user looking to hire a taxi with a driver closest to their location. In US cities, it is illegal to offer taxi services without a license, which is often very expensive. A driver without a taxi license cannot transport someone who hails the vehicle on the road for a fee, thereby offering a taxi service. Uber got around this problem by allowing registered drivers to respond to passengers though its mobile app. A registered Uber driver can start accepting hires by simply logging in to the company’s smartphone app. Customers use a similar app to find an available taxi. Before the internet and smartphones, it was difficult to put a car up for hire. By allowing the market to determine fares, to some degree, Uber chips away at transport inefficiencies. When hundreds of people put their physical assets – cars in this instance – for hire, it creates a marketplace. Uber and most other similar car share schemes also charge the customers’ credit card after a ride, eliminating the hassle of cash transactions. In New York, Uber takes 20-28% of the fare.

PickMe’s business model is identical, except for it not charging a commission for its service of linking taxis with riders, for now. Founder Zulfer says they will introduce app functionality to make it possible for riders to maintain credit or debit card details in the app for cashless payments for taxi hires eventually. Although more than 2,000 taxis are registered and use the service, PickMe does not earn anything for connecting drivers with riders. Its first revenue came when it started to charge a fee for registering taxis on its network.

PickMe was valued at Rs750 million when it concluded its second round of funding in September 2015, just three months after launching the taxi network hub. It raised Rs150 million in funding in the second round, where all its first round investors and four new investors including MAS Capital and Hirdramani Investment Holdings joined. The valuation it achieved in the second round was five and a half times greater than its first round valuation of Rs133 million, achieved in February 2015, just five months before. Payments specialists Interblocks, Lanka Orix Information Technology Services, John Keells Holdings Deputy Chairman Ajit Gunawardene and Ruchi Gunawardena invested in the first round.

PickMe was valued at Rs750 million when it concluded its second round of funding in September 2015, just three months after launching the taxi network hub. It raised Rs150 million in funding in the second round, where all its first round investors and four new investors including MAS Capital and Hirdramani Investment Holdings joined. The valuation it achieved in the second round was five and a half times greater than its first round valuation of Rs133 million, achieved in February 2015, just five months before. Payments specialists Interblocks, Lanka Orix Information Technology Services, John Keells Holdings Deputy Chairman Ajit Gunawardene and Ruchi Gunawardena invested in the first round.

In June 2014, Uber raised $1.2 billion that valued the firm at $17 billion. Other sharing economy behemoths are also seeing similarly high valuations. A year later, Uber is reportedly valued at around $50 billion at present.

Without much revenue, PickMe is dependent mostly on equity to quickly build scale. Funding pays the costs associated with its 60 team members, over half of them engineers building more functionality into its network app. The smartphones for registered drivers were provided free at first and PickMe now charges Rs2,500 for registration. This is its only revenue so far.

Without much revenue, PickMe is dependent mostly on equity to quickly build scale. Funding pays the costs associated with its 60 team members, over half of them engineers building more functionality into its network app. The smartphones for registered drivers were provided free at first and PickMe now charges Rs2,500 for registration. This is its only revenue so far.

“We were careful in getting the right investors in, because we’re not just looking for money, but the capability they can bring,” Zulfer explained, indicating Interblocks – one of the investors – as assisting the firm with payments integration to the PickMe app.

PickMe’s ultimate vision, according to Zulfer, is to promote sharing and ultimately encourage consumers to leave their cars behind. “It’s far more cost effective to use a taxi than drive your own vehicle,” he claims, of fuel, maintenance and depreciation, and the difficulty finding parking space. Despite these drawbacks, people stick with their cars as the alternatives like public transport or taxis are inconvenient and often impractical.

PickMe – like Uber and other taxi apps – aims to change the equation of taxis being inconvenient and uncompetitive by targeting inefficiencies in the current model. Sri Lanka has around 600,000 tuk tuks, according to Zulfer, of which around 100,000 operate around Colombo and its suburbs. Tul tuks here operate under one of three models – those based out of a taxi stand, those registered with a taxi service whose call centre assigns hires and those that run independently. All these drivers have one thing in common – idle capacity and an under-utilized asset.

Sharing assets even with relative strangers has been happening for ages but the issue of trust has limited how widely people were willing to share. Sharing stuff for a fee allows those who own these expensive assets, which they aren’t personally using all the time, to make some extra money. It also allows people who want access to these assets to save money. It’s less expensive than buying or renting, in this instance, a car.

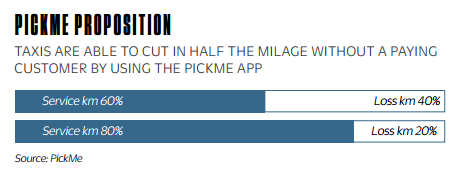

There have long been sharing companies who would, for instance, buy a fleet of cars and put them on the street for people to share, for a fee. This new phase of the sharing economy, however, has taken that to the next step, allowing people to rent from each other. The risk of buying a fleet of cars in the first place is eliminated. For a driver, PickMe minimizes the mileage loss of repeatedly circling seeking their next hire. Zulfer says, “We have halved the industry’s mileage loss and we think we can cut it further.” From a driver’s perspective, this is a great advantage because PickMe assigns the passenger located closest to the vehicle. This not only benefits the driver, but also passengers who generally call for a vehicle in a hurry. Anyone with an Apple or Android smartphone can download the PickMe app, and after registering some basic details with the company through the app, can start ordering taxis. The sharing economy, the peer economy, the asset-light lifestyle or collaborative consumption, as this trend is now being referred to, is unique because of the use of technology to reduce the transaction cost of renting or sharing things from other people over the internet. Cars and homes – where people have most of their equity tied up – are the most shared things.

There have long been sharing companies who would, for instance, buy a fleet of cars and put them on the street for people to share, for a fee. This new phase of the sharing economy, however, has taken that to the next step, allowing people to rent from each other. The risk of buying a fleet of cars in the first place is eliminated. For a driver, PickMe minimizes the mileage loss of repeatedly circling seeking their next hire. Zulfer says, “We have halved the industry’s mileage loss and we think we can cut it further.” From a driver’s perspective, this is a great advantage because PickMe assigns the passenger located closest to the vehicle. This not only benefits the driver, but also passengers who generally call for a vehicle in a hurry. Anyone with an Apple or Android smartphone can download the PickMe app, and after registering some basic details with the company through the app, can start ordering taxis. The sharing economy, the peer economy, the asset-light lifestyle or collaborative consumption, as this trend is now being referred to, is unique because of the use of technology to reduce the transaction cost of renting or sharing things from other people over the internet. Cars and homes – where people have most of their equity tied up – are the most shared things.

Despite being monikered “Tuk Uber” on the Internet, PickMe has no links to any similar ride sharing or taxi app companies. “We want to solve problems. Passengers have issues and drivers have issues. We want to organize this industry, so the stakeholders benefit,” Zulfer explains the vision.

Despite being monikered “Tuk Uber” on the Internet, PickMe has no links to any similar ride sharing or taxi app companies. “We want to solve problems. Passengers have issues and drivers have issues. We want to organize this industry, so the stakeholders benefit,” Zulfer explains the vision.

Most taxi services prioritize lucrative long distance hires and keep other passengers waiting. However, PickMe offers complete transparency. A user can see where PickMe vehicles are available in a map on the app. The system is transparent, and to the potential passenger, the taxi’s location is visible in real time. It works with GPS, available in almost any smartphone.

Internet-enabled matching of owners and renters isn’t limited to taxis. Firms as varied as Uber, Snapcar, Getaround and Lyft for car sharing, Airbnb for home sharing, Kickstarter for funding creative projects, Angellist allowing someone to become an investor in a company, Micro-loan sites like Kiva and Etsy to buy from someone manufacturing by themselves are all leveraging the internet to create networks, allowing people to share stuff in a marketplace that they create. There are hundreds of other such firms – from those helping people share camping spaces in Sweden to human genome sequencing systems in Australia.

Established companies are also joining in by sharing their excess capacity, but the sharing economy is most exciting and holds the greatest potential for people renting things from each other.

Sharing a car is not the same as carpooling because technology has reduced transaction costs, making sharing assets with strangers easier and therefore possible in a much larger scale.

Passengers are usually calling multiple taxi services before they find one willing to take on the hire. They then have to direct the driver on the phone to their location. “We provide the taxi that is closest to you, rather than allocating the vehicles on the network on a first come first serve basis.”

New York University, Stern Business School’s Professor Arun Sundararajan – who has been studying internet-enabled surge of the sharing economy – says it’s too early to know how ramped up sharing will impact the economy in the long run. However, besides the reduction in transaction costs, he also identifies the better use of financial capital, the positive effect of increased economic activity, greater productivity from capital assets and the variety that new consumption options bring as some of the benefits.

Colombo’s taxi companies own few or none of the cars that they offer for hire. PickMe wants to start attracting these cars to its network. With its 2,000 registered vehicles, PickMe is currently the second-largest network. (The largest is Sonit, which primarily operates tuk tuks, in addition to mini cars. But even they are slowly defecting to PickMe, says Zulfer.) But it’s still overwhelmed by the demand. The platform currently includes 16 small taxi operators, in addition to independent drivers, mostly tuk tuks. “We’ve opened a door of opportunity. They have seen the value and people literally queue up to get a device,” Zulfer says. PickMe’s waiting list is over 1,000 drivers because the firm has run out of smartphones that it issues to each driver. A new shipment is on the way, assures Zulfer.

“These individuals are essentially entrepreneurs,” says Zulfer. On average, a tuk tuk driver earns around Rs1,500 a day. But those using the PickMe, Zulfer claims, earn between Rs5,000 and Rs7,000 a day in Colombo. How much a driver earns depends on how well he positions himself to meet potential demand. To earn Rs5,000, a tuk tuk driver must rack up 143 revenue kilometers.

PickMe’s drivers undergo mandatory training on etiquette and service prior to registration. The registration requires a police report, a letter from the Gramasevaka, and copies of their license and insurance before they are included in the platform. This is coupled with a rating feature on the app that allows users to rate each driver for good service. “At the end of the month, we reward the driver with the best rating. This is an incentive,” Zulfer adds.

Much more is possible. Currently, taxi fares are fixed except for a nighttime premium. Taxi apps can offer dynamic pricing depending on demand, congestion and even driver rating. More part time drivers, who prefer to drive for a few hours a week after their regular job and during the weekend, can also be included. Because pricing can be adjusted to be demand driven, it makes sense to work even during rush hour when fares are likely to be higher.

Much more is possible. Currently, taxi fares are fixed except for a nighttime premium. Taxi apps can offer dynamic pricing depending on demand, congestion and even driver rating. More part time drivers, who prefer to drive for a few hours a week after their regular job and during the weekend, can also be included. Because pricing can be adjusted to be demand driven, it makes sense to work even during rush hour when fares are likely to be higher.

PickMe is not taking on the organised taxi services industry, but only the inefficiency inherent in the model it assures. “They think we’re a threat to them, but we’re not. We want to work with the operators,” Zulfer exclaims, adding, “Freelance drivers can join us, but the taxi industry is the one that can gain the most by working with us.”

Zulfer says the looming entrance of Uber to Sri Lanka doesn’t daunt him. Uber has advertised its intention to recruit for key positions for a new Sri Lankan unit. Zulfer adds that his team has analyzed models of several taxi apps like whacky US operator Lyft, Ola in India and Malaysia’s GrabTaxi when building a business model for Sri Lanka. “Our apps are all multilingual – including Sinhala and Tamil,” he highlights. The touch buttons on the device have been made larger and colour coded to accommodate drivers not used to technology.

At Rs35 per kilometer for tuk tuks, Rs40 for mini cars and Rs60 for sedans, PickMe’s rates are lower than the market. The firm may skim 20% off mileage as soon as it enables payments on its app. Drivers on the network have been sounded out already that PickMe intends to start charging a commission for the service they provide, based on kilometers driven for individuals and possibly based on a subscription for taxi companies. Zulfer is tightlipped about the mileage being clocked on its network by taxis. However, if each of the 2,000 vehicles clocked 80 revenue kilometers a day charging Rs35 per kilometer and PickMe skimmed 20%, the firm’s daily revenue would be Rs1.1 million.

Some car sharing marketplaces have been banned in Europe and various conditions and taxes that apply to large hotel chains have been imposed on home sharing in some US and European cities. Legislators are generally uncertain about how to deal with these sharing economy firms, which reduce costs of services for most consumers but threaten major disruptions. They are also difficult to tax and impose safety and other regulations on.

Some cities would like to regulate home rentals, as they were a hotel. They would like to charge tourism taxes and implement other safety requirements that apply to hotels. Taxi services have come under fire from regulators and taxi drivers who want to protect their monopoly.

These fights are happening because the sharing economy is no longer a fad on the fringes, but a big enough target that it’s seen as being worth fighting against.