Mobile phone operators blithely assume that soon almost everyone will have a Smartphone, and these subscribers will then demand faster and more reliable mobile broadband. Indeed, more mobile users are buying Smartphones as handset prices decline and functionality improves and using them to access social media and the internet.

However, confidence on mobile broadband maybe slightly misplaced. There are two reasons that may prevent mobile broadband becoming the hit that network operators and investors expect it to be. Firstly it’s pricing. Sri Lanka’s mobile broadband or data rates are among the lowest in the world. This is great right now for bandwidth hungry subscribers but bad news for investors and telcos that may struggle then to finance costly network expansion and upgrades in the future.

Secondly telcos, in some markets, are being relegated to ‘dumb pipes’, useful for the network connectivity but little else. A subscriber who considers her mobile service provider a ‘dumb pipe’ will abandon the telco for the flimsiest of reasons, like the services of a slightly cheaper rival or one offering marginally better connectivity.

So, while broadband penetration has far from plateaued, making a profitable business out of the opportunity is far less a certainty. Unless, that is, a telco is able to think of this conundrum anew.

Sri Lanka isn’t a mass affluent nation and it will take more than a decade for it to ease in to the upper middle-income league tables, when most of its population will have enough disposable income to afford lifestyles comparable to those enjoyed by the populations of Malaysia or Thailand. In low-income countries corporate titans generally ignore the millions of poor because of their weak spending power.

However, the less affluent are also upwardly mobile in Sri Lanka, and represent trillions of rupees in spending power. On the rare occasions private sector firms have created products that meet the needs of the less affluent they create for themselves a market with millions of consumers and little other competition.

Dialog, a unit of Malaysia’s Axiata, has been the rebel in the Sri Lankan telco industry. In 1997 it defied norms by discarding an industry focus on high revenue per user, instead driving mass adoption and focusing on maximizing profit per minute. The second major departure from the established telco model came in 2005. Instead of looking at its growing operation then as a portfolio of businesses addressing communication needs, its Chief Executive Hans Wijayasuriya took a converse view of the business as having a portfolio of competencies. “We changed our vision to be the undisputed leader in the provision of multisensory connectivity for the empowerment and enrichment of Sri Lankan lives and enterprises,” recalls Wijayasuriya. A telco only seeing itself as having a portfolio of businesses like broadband and satellite television may have set out to be a multimedia service provider as opposed to that of multisensory connectivity.

At the time Wijayasuriya felt the need to spell out the breadth and depth of what Dialog’s future was going to be. For Dialog multisensory meant to touch human senses be it sight and sound or the senses of learning, intellect, emotion and connecting, all these for empowerment and enrichment of lives, Wijayasuriya says. Sri Lankans all over the country were the vortex around which Dialog was preparing to innovate.

For its affluent users, perhaps less than five percent of customers, Dialog offers value-added services like international roaming, rich content and fast mobile internet services. With relatively little innovation telcos are able to build business products that add value to wealthy customers. However, to innovate around the needs of the less affluent requires ‘value adaptation’, Wijayasuriya says.

For a private firm to be able to profitably meet the needs of the poor, empowers those economically marginalized segments of the community by making them customers rather than cases for charity. “We have to value adapt to make our services absolutely affordable, relevant and easy to reach for the consumer,” emphases Wijayasuriya during an interview.

The frugal approach to innovation is working. Around the country Dialog has recruited and trained thousands of corner shop owners to become an interface between the technology and the customers who want to access services. Through mobile money services it has democratized small value transactions, facilitated cash transfers and bill payments.

Mobile money allows cash to travel as quickly as a text message. Broadly two types of transactions are possible with Dialog’s mobile money service called eZ Cash. Users of the service can, by topping-up an account called a wallet with electronic money, send money to each other, pay utility bills, purchase products at a store, pay an insurance premium, or make purchases on the internet. EZ Cash customers can also seek assistance from one of Dialog’s 13,000 eZ Cash merchants. A customer by handing cash to a merchant – usually a shopkeeper – can have a utility bill paid, cash transferred to a friend or pay an insurance premium.

Village corner stores – equipped with an eZ Cash networked mobile phone – are now rather like bank branches. A customer can load electronic money credits from eZ Cash registered corner stores or supermarkets island-wide. A Dialog text immediately confirms the credit. On average there are Rs2 billion a month in Dialog call credit top-ups and a growing volume of electronic money.

Services like these make mobile phones more than yuppie play things. In the last decade they have empowered millions of rural poor people compensating for poor public transport and difficulty in obtaining information about government services and making small businesses more efficient. The opportunity in the middle and the bottom of the income pyramid is one that is generally ignored by the private sector who often don’t have products that can be adapted to be useful for those segments.

If the economy of this country is to grow rapidly the trick is to mobilize the middle and bottom, according to Wijayasuriya. “It means the middle and bottom of the pyramid must be able to do business with the top. What comprises the top? The large enterprises like financial services and healthcare, education, trade and the government.” This is the major economic arbitrage that Dialog sees, present only in countries lacking infrastructure that connects masses to markets, other businesses and the government.

“So in our emerging markets you have economic arbitrage,” agrees Wijayasuriya because infrastructure supporting commerce is weak at the middle and bottom of the income pyramid. “If technology can bridge the gap and bring the top of the pyramid closer to the middle and the bottom then it will have significant spinoff benefits to individuals as well as the country.”

Profitably meeting the needs of the poor is as good for the corporate bottom-line as it is good for the soul. It’s great for the soul because the poor are empowered as customers rather than supplicants of charity.

Charity, corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainability and corporate citizenship are just some of the terms firms associate with what they see as their moral responsibility to be good. Often firms respond to this challenge in one of three ways. Firstly with corporate philanthropy: often meaning they write a big fat cheque to the chairman’s favorite charity. But firms are now realizing that arm’s length philanthropy isn’t acceptable to stakeholders anymore.

Secondly firm’s approach CSR as a branch of risk management. No big firm likes controversy over, for instance, an allegation that its activities have damaged the environment. To avoid controversy and bad press from a potential mishap companies like to proactively address risks that surround their businesses. As a CSR response to its potential environmental impact a firm may invest in a state-of-the-art effluent treatment facility and gloat about this in their annual report, highlighting their social conscience when in fact all they are doing is managing business risk. This is now a popular approach to CSR because it makes far more business sense than the first one.

However, both these approaches are rather defensive strategies compared to the third; which is that companies can find perfectly viable business opportunities providing services to sections of society that are now ignored because of their weak spending power. Building CSR in to the corporate strategy would make it part of the firm’s competitive advantage, something Dialog has achieved but few other firms can boast about here or overseas.

By market capitalisation and revenue Dialog is neck and neck with Sri Lanka Telecom PLC, a majority state-controlled telco. In 2012 Dialog and SLT group both had revenue of Rs56 billion. However, Dialog was the more profitable of the two, earning Rs6 billion versus Rs4.5 billion at SLT.

The industry, however, has been hamstrung since 2007 because of its suicidal tendency to price services too cheaply. In 2010 the telco regulator, the TRC, was compelled to intervene and set floor prices for voice, which at that time accounted for over 90% of revenue at telecom firms, to prevent an aggravation of a bloodbath. In the lead up to the TRC intervention both dominant telcos, Dialog and SLT group’s Mobitel, had seen deep dips in revenue following aggressive call tariff cuts that didn’t generate increased volumes immediately after.

Three years on, anti hara-kiri telco regulations continue almost unchanged. In 2012 the regulator allowed a 25% relaxation of the floor rate imposed on off-network tariffs, “in line with its objective of guiding the industry along a trajectory of rational competition modulated with the enhancement of value delivery to consumers,” Wijayasuriya commented in Dialog’s 2012 annual report. During 2012, industry-wide mobile subscriptions increased almost 11% to 20.3 million connections while fixed telephones decreased by 4.4% to 3.4 million lines.

For Dialog’s strategy of foraying beyond a dumb pipe to succeed it needs robust voice revenue. In mature markets telcos have been relying on broadband or data revenue for decades. Voice in these markets is a freemium service; offered free or charged very little for, within premium service bundles including broadband and pay television. Wijayasuriya admits, “in our markets it’s unfortunately the reverse. That’s where it proves a serious challenge to our pipe business.” Telcos here depend on voice revenues to roll out their high speed broadband and fiber optic networks.

At Dialog, broadband use jumped to 6.7% of customers in 2012 from 4% a year earlier. Stock analysts at CAL Securities, a stockbroker, estimate this will rise to 14% by 2014, judging by the experience of the region.

Ratings agency Fitch, which has assigned a gilt equivalent triple A rating to the stock, forecasts that data revenue from the mobile business will be between 20-25% of the total by 2015. In the second quarter of 2013 the figure was 10% which was double the level in the same quarter of 2012.

“But we have a serious issue to sort out,” emphasises Wijayasuriya, “because the techno-economics of the industry is such that voice usage will convert to data eventually.” He explains that voice revenue now subsidising broadband network rollout will fizzle out in the future. “The growth of the pipes (high speed networks) which underpin the entire ICT sector would be constrained unless we correct data pricing to viable levels.”

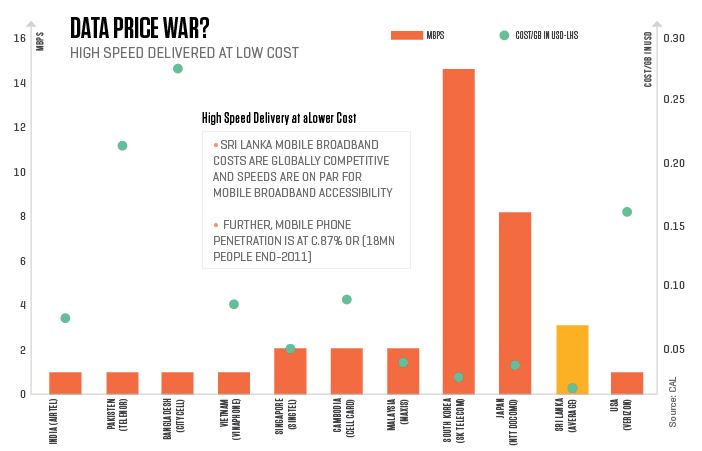

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) recently recognised broadband tariffs in Sri Lanka as the lowest globally. An analysis by stockbrokerage Capital Alliance shows Sri Lankan broadband prices are between half to a fifth of levels in rich Asian countries like Singapore, South Korea and Japan. Other developing Asian nation mobile operators charge between six to twenty times more than users here pay for broadband.

In an interview Wijayasuriya stops short of asking for floor prices for broadband services. Despite murkiness of returns telcos are continuing to invest in broadband. Dialog in 2012 invested $136 million or Rs17 billion taking its total investment in Sri Lanka to over $1.4 billion, the largest by a foreign direct investor.

Despite the so far weak prospects for broadband, parent Axiata Group Berhad of Malaysia in July 2013 supported a $200 million syndicated loan to help Dialog fund capex and lower costs. Axiata also provided a corporate guarantee for Dialog’s previous tranche of debt and extended a shareholder loan in 2009 when Dialog was under financial stress, according to Fitch.

Fitch expects Dialog’s capex to remain high at between 30% and 40% of projected revenue in 2013 and 2014, mostly for expanding its data capacity and quality. Wijayasuriya expects that less than 10% of capex will be used out in developing the firm’s inclusive digital services.

Part of the capex will be spent on securing alternative access to international bandwidth through the Bay of Bengal submarine cable, which will be operational by end-2014, and will provide Dialog with cheaper access to the rest of the world, according to Fitch.

These investments come on the back of Dialog already having spent $35 million for fixed and mobile spectrum to launch high speed 4G services. It paid $12 million to the TRC to re-farm spectrum fixed-line operator Suntel and Sky TV owned – both of which it acquired – to be used for fixed-line 4G. In a TRC conducted auction it also acquired mobile 4G spectrum for $23 million.

Sri Lanka is now a market primed for data and saturated for voice. The hara-kiri approach to data pricing, however, is undermining not just industry investment prospects but also the speed at which crucial ICT infrastructure can be built. However, operators have tough choices. They need to ensure pricing is appropriate for optimal network utilization, and keep an eye on market share and the dilution of profits due to the substitution of voice revenue by low margin data.

Dealing with these challenges ensures the opportunity for companies to innovate in ICT and technology’s ability to impact lives is left open to everyone.