How to Rob a Bank

State banking is a cosseted affair. In good times the profits reinvested are just enough to grow the capital bases and in bad times the government cleans up after them. The treasury has bailed out the two largest state owned commercial banks – BOC and People’s Banks– six times in the past three decades. The rules that govern the financial […]

State banking is a cosseted affair. In good times the profits reinvested are just enough to grow the capital bases and in bad times the government cleans up after them. The treasury has bailed out the two largest state owned commercial banks – BOC and People’s Banks– six times in the past three decades. The rules that govern the financial sector apply equally to all banks. However the country’s biggest financial institutions are so closely held that they are arms of the government.

The three largest banks by assets and a number of other financial institutions are treasury controlled. Of the pension funds, also financial system components, the two largest by far, the EPF and ETF are government managed.

Although profitable, the state owned banks are also struggling. Their retained earnings are inadequate to fund their balance sheet growth, reliance on lending to the state has alienated private firms; the country’s main change agents, and their cosseted executives and boards are disengaged from modern banking. While private banks are grabbing market share, the state ones are only slowly moving towards becoming real institutions. In the fringes, the state bank crisis is amplified.

Although profitable, the state owned banks are also struggling. Their retained earnings are inadequate to fund their balance sheet growth, reliance on lending to the state has alienated private firms; the country’s main change agents, and their cosseted executives and boards are disengaged from modern banking. While private banks are grabbing market share, the state ones are only slowly moving towards becoming real institutions. In the fringes, the state bank crisis is amplified.

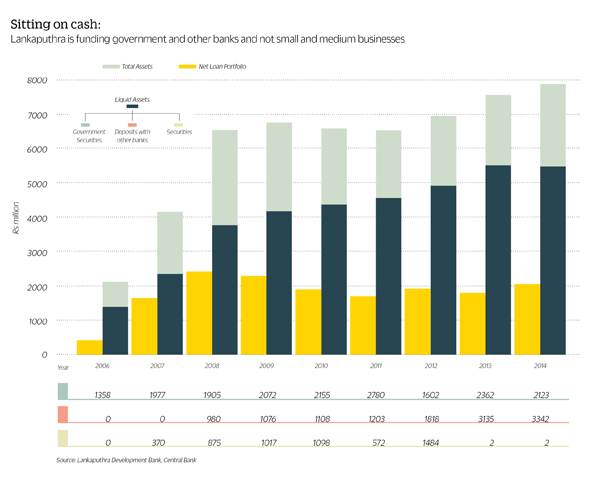

Hyperbole about uplifting small businesses, reviving the rural economy and creating jobs falls flat. It’s at first difficult to see through government owned and profitable Lankaputhra Development Bank’s veneer.

Lankaputhra isn’t really a bank at all, but an institution that has invested most of its government provided capital in the government’s own debt, and on political direction, granted large loans it then made no attempt to recover.

“It is a daylight bank robbery,” bellows Lankaputhra’s new Chairman Lasantha Goonewardena who was appointed in January 2015 in an interview. Lankaputhra hasn’t recovered a single installment on Rs1.2 billion lent to 15 firms and cooperatives. This includes Rs555 million in loans to nearly defunct apparel factories, by the bank without recognizing these as assets in the balance sheet. Except one, the rest have not been repaid even partially.

The bank’s large now non-performing loans were granted during the years 2006 to 2009. The bank’s founding chairman was A de Vass Gunawardena, father of parliamentarian Sajin de Vass Gunawardena. In 2008 Sarath de Silva a former banker was appointed chairperson. It was during the tenure of these two chairmen that the bank’s loan book was pulled in to the abyss. Echelon was unsuccessful in tracking down Vass Gunawardena and Sarath de Silva. In 2010, De Silva and the entire board had been replaced.

Lankaputhra’s second chief executive Siromi Wickramasinghe, sister of former Central Bank Governor Ajith Nivard Cabraal said it would be unethical for her to discuss her former employer. She declined to be interviewed. Echelon was unsuccessful in contacting the bank’s first chief executive A T Cooray. Two other directors who held office during the bank’s first three years also declined to be interviewed.

Its current chief executive, Lasantha Amarasekara, who granted an interview for this story, was appointed in 2011.

Loans to troubled garment factories were provided under a Rs730 million treasury facility granted to the bank. An undisbursed Rs174 million under the scheme is shown as a liability in the bank’s balance sheet. However the bank’s chairman or its chief executive were unable to explain how the disbursed amounts were being accounted for. They both reiterated the loans were off balance sheet.

The biggest non-performing loan (not reflected in the balance sheet) is Rs530 million lent to TriStar Apparel Exporters, a firm that was controlled by pioneer apparel manufacturer, the late Kumar Devapura, and is now managed by his family.

The facilities were interest free for borrowers. The Tri star loan did not bring fees or interest income to Lankaputhra. The bank was merely the facilitator for the loan.

A report of COPE – a parliamentary committee with oversight over public enterprises – said in addition to TriStar Apparel Exports other non performing loans by Lankaputhra under the scheme included Rs9.3 million to Keen Wear International and Rs8.8 million to Osaka Garments both of which have gone belly up. The bank had filed court action to recover the outstanding loans from Keen Wear and Osaka Garments before they collapsed, however no action has been taken against TriStar Apparel Exports.

An official with knowledge about the Tri star loan said on condition of anonymity that several rounds of talks had taken place with Lankaputhra in 2014 and 2015 but there was no firm commitment yet from the company to repay the loan. Tri star founder Kumar Devapura passed away in October 2014.

An official with knowledge about the Tri star loan said on condition of anonymity that several rounds of talks had taken place with Lankaputhra in 2014 and 2015 but there was no firm commitment yet from the company to repay the loan. Tri star founder Kumar Devapura passed away in October 2014.

The official further said that Lankaputhra did not aggressively pursue the loan repayments because it had its own non-performing loans to deal with.

The loan agreement between Lankaputhra and Tri star was signed in February 2007. Tri Star Apparel Exports were required to transfer 23% of its shares to the government, appoint competent management with a Treasury official in its board and pay Rs5 million monthly as loan settlement. It is not clear if the company and the treasury adhered to any of these conditions.

Echelon was unable to contact a responsible Tri star company official. Its main factory in Maligawa Road in Ratmalana functions but none of the telephone lines listed on its website work. Security officers at its Ratmalana headquarters said its management is only contactable on their mobile phones. They refused to share a mobile phone number of a responsible Tri star official who could answer some questions.

Only one firm that borrowed Rs7 million under the scheme, has repaid the loan.

The 2012 COPE report, the only one by the parliamentary oversight committee examining Lankaputhra, said that loans had been granted without acceptable valuation reports and in contravention to Central

Bank guidelines.

Lankaputhra received Rs1.5 billion equity from a government budget allocation, when it was established in 2006.Its vision was to lend to small and medium sized businesses, support the rural economy and create jobs in the process. In January 2008, it absorbed state owned SME Bank, though a share swap. SME bank, was also established at the same time as Lankaputhra with an identical amount of capital. The merger doubled Lankaputhra’s capital and made it possible for it to meet the new regulatory minimum of Rs2.5 billion. A year later, in January 2009, Lankaputhra absorbed another government institution, the Private Sector Infrastructure Development Company Limited.

Lankaputhra received Rs1.5 billion equity from a government budget allocation, when it was established in 2006.Its vision was to lend to small and medium sized businesses, support the rural economy and create jobs in the process. In January 2008, it absorbed state owned SME Bank, though a share swap. SME bank, was also established at the same time as Lankaputhra with an identical amount of capital. The merger doubled Lankaputhra’s capital and made it possible for it to meet the new regulatory minimum of Rs2.5 billion. A year later, in January 2009, Lankaputhra absorbed another government institution, the Private Sector Infrastructure Development Company Limited.

In the financial year ending December 2014, the bank reported Rs179 million profits the ninth straight year since founding in which it has been profitable. What appears to be the dichotomy of almost half its loan book being non-performing and the bank’s profitability is explained, easily.

Of its Rs7.9 billion asset base Rs5.5 billion are invested in government securities (REPOs) and fixed deposits with other banks. Customer loans are just Rs2 billion. Typically around 60% of a bank’s assets are customer loans but at Lankaputhra it’s 26% and nearly half those are non-performing.

A chunk of its fixed deposit is a US Dollar deposit equivalent to Rs2.4 billion at Bank of Ceylon. This is also a government extended facility which originated from the German government’s development lending agency KfW which the bank is expected to pay back in 2018. These facilities are usually granted to government to support low interest rate lending to identified sectors. However Lankaputhra hasn’t lent these funds. The German Embassy in Colombo said that KfW no longer has an office in Sri Lanka.

Of the bank’s Rs606 million ineptest income in 2014, Rs394 million or (65% of interest income) was derived by investing government provided capital in treasury bills and bonds and the KfW funds in a dollar fixed deposit. The BOC fixed deposit generated over a third of the bank’s interest income (Rs213 million out of Rs606 million interest income in 2014).

Lankaputhra’s capital, including Rs3 billion in government provided equity, retained profits and reserves topped Rs4.6 billion at end 2014. In Sri Lankan banking terms Lankaputhra’s crises’ are at polar opposites of banking challenges.

The first of those challenges is scale; the bank is a Lilliput in the industry. Its Rs7.9 billion assets in 2014 are just 0.12% of banking assets (commercial and specialized banks). Lankaputhra lays claim to just Rs380 million or 0.008% of the banking sector’s Rs4.6 trillion in deposits.

The first of those challenges is scale; the bank is a Lilliput in the industry. Its Rs7.9 billion assets in 2014 are just 0.12% of banking assets (commercial and specialized banks). Lankaputhra lays claim to just Rs380 million or 0.008% of the banking sector’s Rs4.6 trillion in deposits.

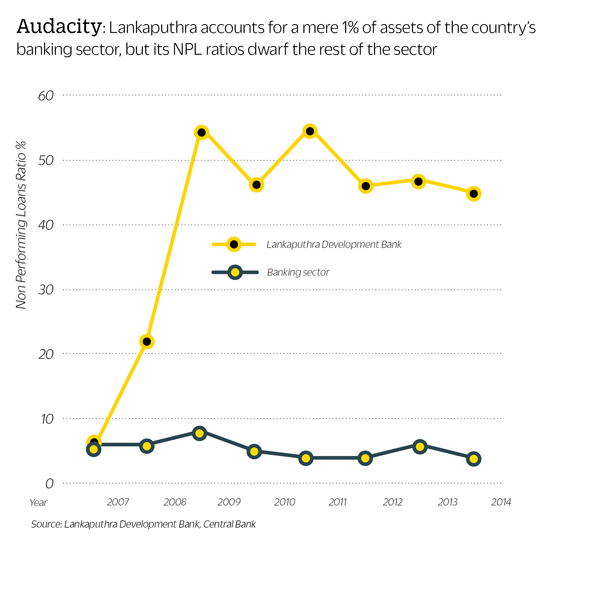

The other polarizing factor is its non-performing loan ratio, which at 44.6% in 2014, is unsurpassed in Sri Lankan banking. The bank’s books don’t recognise the Rs550 million in dud loans arising off the treasury’s scheme to restructure troubled garment factories. Banking industry wide non-performing loans are 4.2%.

Bank loans are split in to two categories, performing or non-performing. If they are non-performing the bank must build up a reserve against the potential loss, this is called a provision. Lankaputhra’s books recognise 663 million in loan loss provisions in 2014. It also had Rs465 million unpaid interest on non-performing loans by end 2013.

Most of its 7,600 customers, have borrowed modest amounts and maintain an excellent repayment record. “Small borrowers only accounted for around 4% of non-performing loans. It is the big players with state patronage who don’t also qualify as SMEs, who have willfully defaulted,” maintains Lankaputhra’s chairman Goonewardena.

It wasn’t a dramatic armed heist nor sophisticated white-collar crime. However Lankaputhra’s dud loans, its shoddy corporate governance and dreadful executive accountability point to wholesale negligence and a criminal breach of trust. Its chairman Goonewardena maintains the bank has been robbed.

Almost all the bank’s large non-performing loans have been granted in the years 2006 to 2009. Echelon has seen documents suggesting these loans were granted under influence of politicians and senior government officials claiming to act on the instructions of politicians.

Lankaputhra’s chairman and chief executive refused to discussindividual loans. However, Goonewardena was critical about the stewardship of the bank in the years since founding to 2009. “Credit and recovery policy manuals and procedures were not followed. The non performing ratio kept rising,” he said, “documentation is a mess and those employed by the previous regime are not helping us trace documents and files of defaulters. Even the officers are incompetent and I don’t think they are adequately qualified. They were just sitting around here.”

“We have managed to bring the non-performing loan ratio down to 39% because we started to recover the loans,” Goonewardena says. The bank’s last published accounts are for the year ending December 2014 which was a period ending just before Goonewardena was appointed.

Of the non-performing Rs300 million is owed by a manufacturer of footwear; on a loan obtained to expand capacity at a tannery and factory in the Hambantota district. It’s unclear if any part of this loan has However it relented when a letter from the President’s office in April 2008 requested the bank, ‘pay your urgent and special attention to this letter of request and take appropriate early action’. The letter to Lankaputhra signed by an Assistant Secretary to the President attached with it a request letter for an enhanced facility from the company addressed to then President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The letter to the president requesting an enhancement to the facility claimed an existing loan from Lankaputhra was ‘promptly being paid’. Loan related documents, some of which Echelon has seen are now being pursued by a special unit of the CID investigating financial crimes. Siromi Wickramasinghe was chief executive and Sarath De Silva was chairman of the bank in 2008 when this letter was issued from the president’s office.

“None of them had paid anything to the bank and we don’t even know whether these funds were used for what they were intended for,” Goonewardena says of the 14 loans about which they have requested the CID’s financial crimes unit to investigate. “There has been absolutely no follow up. In fact one borrower we called had the audacity to tell us that it was not a loan but a grant.”

Borrowers were demanding laxer credit evaluation terms and by agreeing to those Lankaputhra was granting loans to organizations that were not credit worthy. “Recently we found that Rs65 million had been loaned to a company without collateral, its audited financial were not analysed,” claims its chairman Lasantha Goonewardena. The discovery came after Lankaputhra’s board had submitted details of 14 loans they suspect were granted based on political influence to the CID unit investigating financial crimes.

Borrowers were demanding laxer credit evaluation terms and by agreeing to those Lankaputhra was granting loans to organizations that were not credit worthy. “Recently we found that Rs65 million had been loaned to a company without collateral, its audited financial were not analysed,” claims its chairman Lasantha Goonewardena. The discovery came after Lankaputhra’s board had submitted details of 14 loans they suspect were granted based on political influence to the CID unit investigating financial crimes.

“This particular loan was approved on a request of the Presidential Secretariat in October 2014. The file did not have a properly maintained checklist; the asset valuation was missing and there was no CRIB report either.” He says the savings account number provided by the borrower was that of a closed account and only one year’s financial statement had been submitted.

There may be hundreds more like this but looking for them is like locating a needle in a haystack. The documentation is that bad,” Goonewardena said. More iffy loans may lie hidden he suspects. Even after the board purge in 2010, its directors proved supine or foolish. “We began to recover the loans and took maximum action; we began to use our parate execution rights to seize collateral, sent letters, reminders and commenced legal proceedings. Some of the borrowers had not made a single payment. These were submitted to the Financial Crimes Investigation Division (FCID), not merely to recover the loans but also to investigate whether the funds were misappropriated, in other words used for something else or embezzled or even used for political purposes,” he said.

However the bank’s chief executive Lasantha Amarasekara maintains Lankaputhra operates independently. “Sometimes they have spoken over the phone but no one has insisted that I grant a loan,” he says in response to a question about political interference in the period to January 2015.“When things go wrong, like they have, it is easy to blame politicians. They may call us but it is our responsibility to follow due diligence. If it goes to NPL it is the borrower’s fault or our fault for not having done a proper evaluation, follow ups and monitoring; we cannot blame politicians”.

At one time the bank slapped a self-imposed lending cap of Rs20 million per borrower. It also wanted to recruit competent staff; which was scuttled by the bank’s trade union. Staff loans amount to nearly 3% of the bank’s loan book. Public confidence in Lankaputhra has always been marginal. Its deposit base Rs379 million deposit base is proof.

Malaysia’s RAM ratings local unit in its last credit rating report of the bank said key management vacancies had not been filled for several years. These positions included chief operating officer, chief internal auditor and senior finance manager. In nine years, the bank had four chairpersons and three full time chief executive officers and three acting chief executive officers.

Lasantha Amarasekara, the chief executive assures the deposits are safe. “Our deposit base is very small,” he admits. He says the bank has an A- rating from LRA (the successor to RAM), which is a better credit rating than many smaller banks.

“So the bank is long-term stable. But our NPL is high. We have been selective in our lending over the last five years. Annual NPL ratios have been kept below 7%, but we are still weighed down by the bad loans before 2011”.

On the face of it Lankaputhra shouldn’t have landed in so much trouble. Since founding – because of its government control – its board of directors have been independent or those with no direct interest. Despite the government ownership, officials from the Treasury, which holds the shares, were never appointed to the board. Smaller size doesn’t make good governance any less important. In Lankaputhra’s case although an independent board was appointed because it was so closely held, in effect, it functioned like an arm of the government.

On the face of it Lankaputhra shouldn’t have landed in so much trouble. Since founding – because of its government control – its board of directors have been independent or those with no direct interest. Despite the government ownership, officials from the Treasury, which holds the shares, were never appointed to the board. Smaller size doesn’t make good governance any less important. In Lankaputhra’s case although an independent board was appointed because it was so closely held, in effect, it functioned like an arm of the government.

These independent directors haven’t been effective in standing up to imperious chairmen, chief executives and the dim witted political types. Lankaputhra’s balance sheet is marked with those examples. For all their gravitas, it’s also difficult to miss the humour in all this. An internal audit memo handed to the board on 1st April 2015 deals with a Rs75 million loan granted to a Trincomalee based fishing cooperative backed by a request from the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) organizer in the area, to purchase boats. Investigations appear to indicate that three members of the SLFP organiser’s family, including one who was dead, received loans to purchase deep sea fishing boats. Many of the 17 boats purchased are missing the others are in bad shape.

Taxpayers who ultimately bear the cost of this will be forgiven for their snigger. Lankaputhra is tragic more than it is comic.