Meet the go-to guy for economic forecasts

Early in her reign, Russian Empress Catherine the Great’s attempts to mitigate the oppression of serfdom and reform the outdated legal code, foundered against the might of the nobility, the Imperial Guard and the Orthodox Church. In exasperation she explained the challenge to French philosopher and friend Denis Diderot, “You work only on paper which […]

Early in her reign, Russian Empress Catherine the Great’s attempts to mitigate the oppression of serfdom and reform the outdated legal code, foundered against the might of the nobility, the Imperial Guard and the Orthodox Church. In exasperation she explained the challenge to French philosopher and friend Denis Diderot, “You work only on paper which accepts anything, is smooth and flexible and offers no obstacles either to your imagination or your pen, while I, poor empress, work on human skin, which is far more sensitive and touchy.”

It’s much the same gripe that economic policy setters and governments have of their critics. Policy prescribing economists are free to dream up various versions of utopia, to write newspaper columns on those views and address impressionable gatherings of the economic illiterate on the ease with which these can be implemented.

Amal Sanderatne is not a government policy maker or an economist doing talk show rounds and newspaper columns, prescribing economic policy. Sanderatne is an economic forecaster. In fact he refuses to be drawn in to addressing policy challenges facing the Sri Lankan economy, except to endorse an obvious weakness like the destabilising effects of large budget deficits. However in just the last year he accurately forecasted the rupee’s appreciation from the Rs132 levels to the dollar and also called the decline in bond yields.

These and other contrarian calls has set him apart from others who either don’t track the economy as closely or shy away from hard calls that Sanderatne often stakes his reputation on.

Forecasting outcomes are particularly hard because unlike physical sciences economists can’t run real time experiments. Globally economists have a patchy record at forecasting.

Not even experts including Nobel Prize winners can agree on which theories work, firstly as policy prescriptions and secondly in use for economic forecasting. The complexity comes from the difficulty in predicting the behaviour of actors and their motivations. After all not all human behaviours are mercenary. Outcomes are influenced by variables too challenging to model. The Socratic principle of the unknown, unknowables also bears great significance.

Dissidents also point to the glaring failure of economic forecasters to predict the financial crisis, giving credence to John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation that “the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.”

The challenge to forecasting here is sometimes far more rudimentary than can be applied to some model. Sanderatne says “forget the forecasting, the key is to understand what’s going on right now. More than why it’s happening, it’s about what’s happening?” Sanderatne studies economic history both in Sri Lanka and elsewhere and also relies on intuition and judgment as he does on quantitative data analysis. He keenly observes Central Bank reactions and what levels of reserves, for instance, they are comfortable with. “You can see how they react to what happens this time around to how they reacted in 2008. You can draw similarities; sometimes you can see monetary policy behavior patterns.” Understanding how the central bank will react or act is something that is very important explains Sanderatne about his pragmatic approach.

With experience he is getting better at knowing what is relevant and what to discard. “Sometimes the intersection of trends in varied data will help us understand what might happen next, as a result of these past relationships, we sometimes feel we can have a high level of confidence in making a call.”

With experience he is getting better at knowing what is relevant and what to discard. “Sometimes the intersection of trends in varied data will help us understand what might happen next, as a result of these past relationships, we sometimes feel we can have a high level of confidence in making a call.”

Economists – for the most part – believe that prices move towards equilibrium, a crucial assumption used in models and forecasts. The fact that economies or markets will reach equilibrium or be fairly valued is something contrarians reject. On equity markets Sanderatne points out he is a contrarian, believing that markets either overshoot or overcorrect. There also is an inverse relationship between GDP growth and stock markets, he says. “You can’t draw this direct line. I have made this point to clients; high GDP growth in the past in many countries has meant low performing stock markets.” Armchair economists like op-ed columnists have many useful explanations to what happens –after the event. After all it isn’t hard to offer what appear like plausible explanations to what has happened. Op-ed columnists would argue they are just that; opinion writers. However, attempting to forecast the future economic trajectory is not akin to economic commentating.

A professional analyst or economic forecaster – without other means but for corporations paying for their insights – face far greater pressure than do economists depending on the largesse of think tanks, academia or the business press. On the one hand forecasters are challenged by the inexact science that is economics which they have to grapple with, and on the other hand their clients – who don’t much care for policy advice – will demand reliable forecast on the exchange rate, inflation, interest rates and GDP growth.

Forecasters – unlike policy economists – don’t merely work on paper which offers no obstacles to imagination. Forecasters are only as good as their last call, something Sanderatne likes to point out about the caprice with which they are sometimes regarded. A deep understating of the economy and how it will respond to policy and outside shocks isn’t straightforward knowledge. Sanderatne describes economic forecasting as predicting the outcomes of the intersection of various actors in the economy including investors, government and consumers. “I’m not tying myself to being Keynesian, Monetarist or Austrian or relying only on one approach such as using econometrics and not using behavioral finance. I use a mixture but importantly I’m pragmatic,” explains Sanderatne during an interview at his office consisting of a compact workspace for analysts and a boardroom.

Econometrics based forecasts – which marry economics to mathematics and statistics – in Sri Lanka is particularly hamstrung compared to advanced countries due to the lack of detailed, reliable data sets going back many years. “Here, that kind of visibility is limited, you can work with your models, but the results you get might not be what you expect,” explains Sanderatne of the limitations.

He isn’t the only economics forecaster for Sri Lanka’s economy. State and quasi state agencies like the finance ministry and central bank provide forecasts and update those frequently. So do think tanks like the Institute of Policy Studies and lending agencies like the IMF, World Bank and ADB. Large international banks like Standard Chartered, Citi and HSBC also have teams looking at Sri Lanka’s prospects for growth and risks of inflation for the benefit of their clients.

Sanderatne’s career as an Economist started with Jardine Fleming’s Sri Lankan unit – but since he has had varied experience in investment banking, equity analysis and even management consulting since setting up Frontier Research in 2003. However it’s only in 2007 that Sanderatne honed in on economic forecasting as the core of his business. “Pre 2007 I didn’t really know what my business was, I was advisor cum consultant,” he explains. Sanderatne returned to Sri Lanka in 2002 following a posting in Singapore with JP Morgan, after Jardine Fleming which was acquired by JP Morgan closed the Sri Lankan unit in 2001. In the first year he consulted with DFCC which was then handling the IPO for Sri Lanka Telecom. By 2006 he estimates he had around five clients who were paying him for regular economic forecasts which topped 10 when the war ended.

However Sanderatne, who is aided by a team of young analysts, can shift from an ambivalent view to a strong one in quick time like he did in the case of the Rupee this year. In early March 2012 he said “there is a near equal probability the rupee will appreciate or depreciate from the current levels” but days later on 21st March 2012 a new report proclaimed, “We are Sri Lanka Rupee bulls,” when it had become apparent to Sanderatne that the economy and imports will slow down.

“I get this a lot; ‘you are more optimistic than your father’,” he says of how his forecasts are contrasted with opinions of his father’s–a former Central Banker – who writes an economics column in the newspaper. “I totally agree with the longer term issues on the underlying structural challenges and debt build up but still on a one year horizon in March 2012 we believed you could be bullish on the rupee” he says. Staying out of the policy debate – which perhaps requires some discipline to achieve – Sanderatne feels has given Frontier clarity and he is almost amused with the outcome. “There is the highly optimistic central bank and the policy economists who are gloomy, and here we are switching sides.”

Economic forecasters can miss things despite taking many factors in to account, because they have failed to pick the few relevant ones. Sanderatne is clear that he was late in making a call that the Rupee will have to weaken from its second half of 2011 levels. “By January 2012 everyone knew that the rupee had to go (depreciate), but I’m talking about the fact we did not make the call early enough,” explains Sanderatne of the sort of insight he consistently tries to provide his clients. The shock depreciation proved devastating for some listed companies due to exposed dollar positions on their balance sheets. “We did a bad job to have missed the possibility of rupee depreciation in late 2011”, he says but points to over 90% client retention over the years as an overall guide to his track record.

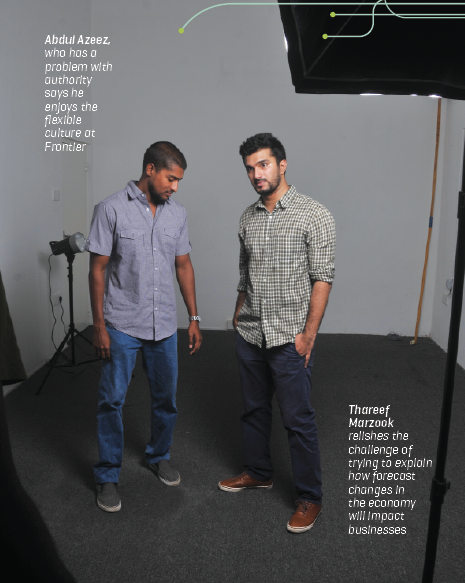

Sanderatne says the 30 plus clients subscribing to his economic forecasts now are attracted by his team’s ability to explain how forecast changes in the economy will impact their businesses. “We make economics accessible to clients,” explains Sanderatne whose team helps craft relevant and customized presentations to each client. “We distil the macro environment to the corporate,” explains Thareef Marzook who is Frontier’s lead research economist. Marzook is intrigued by Amal Sanderatne’s unconventional approach to the subject which he thinks works here. “Especially in an environment such as ours, where you can’t always apply the same methodology you apply in other markets,” he says.

In the past it was mainly Sanderatne who used to present economic views at meetings. But since a few months back, for the most part the presentation of Frontier’s view is done by the other Economists at Frontier, while Sanderatne steps in if needed to deal with the many additional questions and clarifications that clients have. Abdul Azeez a Frontier economist explains that the challenge is about making it research relevant. “A company won’t be run by economists. So you need to take an economic concept, relate it to Sri Lanka and present it in a manner that they understand and also in a manner that’s relevant to them.” Marzook and Azeez are the two senior most members of Sanderatne’s economics team.

Sanderatne believes Frontier’s independence and the fact that it has no agenda are appreciated by clients. “I’m not taking policy views and that maybe my strength. I’m concentrating on what will happen, I have trained myself to do that,” says Sanderatne who makes all the economic forecasts but is supported by his team with data, customization of client presentations and reports and delivery of presentation views.

Frontier clients don’t expect harangue reports that give detailed calls on every other piece of economic data like the Central Bank, a think tank or a foreign donor agency would. At best Sanderatne will be offering one strong view, but one that is also practicable and for a client a chance to make some money. “When there are opportunities I tend to highlight them,” he explains.

Often forecasts focus on exchange rates and interest rates which have wide appeal, inflation which primary dealers of government debt closely watch and GDP growth, useful for diversified companies and any business making sales budgets. After the calls on the exchange rate and falling bond yields, which have come to pass, Sanderatne says he currently holds no strong views. “Suddenly two weeks from now we may see an opportunity in the bond market. It may be bearish or bullish and it can be a strong view.”

In hindsight some of Sanderatne’s calls look disarmingly simple like the one on Rupee appreciation based on his expectation of an economic slowdown and falling exports. Economists build imaginary scenarios on simplified assumptions, like the impact a cocktail of higher interest rates, declining consumer spending and reduced imports will have on an economy. Sanderatne – because he has a close pulse of some of the island’s largest corporations – has an advantage over others looking at the country from afar.

Sanderatne is upfront with his forecasting philosophy and the fallibility inherent in what he sets out to do. In presentations to clients introducing Frontiers services he quotes Karl Popper a philosopher, on “giving up the idea about ultimate sources of knowledge, and admit that all human knowledge is human; that it is mixed with our errors and prejudices…”

Economic forecasting started at Frontier almost by accident when Sanderatne was requested to provide a quarterly update to a client who he met while doing a one off consulting assignment for them. Soon another firm linked to the same group also signed him up.

“They (Frontier’s clients) understand how we do it and they know we can make mistakes, they also know I have been doing this for a long time and that this is our bread and butter,” he explains of the significance of economic forecasting in his small business which employs eight analysts. Sanderatne says he likes to hire young prodigies. “This is like the Silicon Valley culture. At 28 you are really old,” says the 36 year old Sanderatne.

The unique work culture allows Frontier employees to choose their own work hours. “It’s very flexible and that’s perfectly rational because, it’s about getting the work done, there are no rules that don’t make sense,” according to Azeez who claims he has a problem with authority generally but that at Frontier the flexibility is liberating.

Sanderatne’s economic forecasts are the most sought after by private sector firms. Like all forecasters he is trying to figure how rational individuals respond to incentives and apply that to macro economic data. Leaving out political and ideological baggage has perhaps helped him draw clear forecasts out of an otherwise perverse and foggy climate.